Standardizing Carbon Credits for High-Quality Mitigation Outcomes – #4b

Buy-Side Commodification Delivers Emissions-Equivalent Credibility

Carbon offsets are riddled with quality issues and have a historically-abysmal track record of efficacy. Despite ~30 years of certifiers iteratively improving credit supply methodologies, academic research and journalistic exposés continue to call out inaccuracies. Carbon markets (as a concept) take the brunt of the reputational damage and loss of trust even when an article points to a specific certifier’s errors.

Carbon market efficacy challenges unnecessarily reduce demand for what could become an effective climate solution. To unlock its true potential as a credible tool for achieving net-zero emissions, markets need a new approach to meeting demand for carbon credits. An approach that enables buyers to purchase credits with confidence and without becoming supply-side experts. An approach based on transparent, quantifiable metrics assessed on the buy-side of credit markets to commodify credits. Carbon credit buyers and suppliers need an industry-wide quality standard to ensure climate outcomes are directly proportional to the emission being offset.

Today’s markets delegate the responsibility for quality control by trading ‘certified’ carbon credits as if they are commodified. This approach exposes the market to two kinds of risks it must begin managing to increase credibility and end the onslaught of bad press: 1) uncertainty mismatch and 2) apathetic commodification.

The uncertainty mismatch is simple to describe. An emitted ton of CO2 is usually easy to quantify (precisely measured) with high certainty (low variance). Conversely, the CO2 impacts of carbon credits can be difficult to measure with highly variable results. Offsetting a well-quantified emission with a poorly-quantified carbon credit is intuitively illogical if the objective is substantiated climate action. For example, planting 1tCO2 worth of trees that are at risk of fire, disease, or time does not counterbalance 1tCO2 emitted from combusting coal.

Buy-side market actors often take an apathetic approach to carbon credit supply. Accepting credit supply at face value, insofar as certification is granted, commodifies credits by omission. Or rather, the market leans into a “buyer beware” approach with no “lemon law” or other clear recourse. Commodification failures are understandable of course; planting 1tCO2 worth of trees is not measurably equivalent to 1tCO2 of DAC+Storage is not measurably equivalent to 1tCO2 of enhanced weathering. Although some markets offer portfolios of credits to reduce risk and others offer only the most permanent credits, even a few apathetic marketplaces reduce the credibility of the entire market concept1.

Uncertainty mismatch and apathetic commodification have the same solution – a buy-side quality standard that works in tandem with supply-side certification.

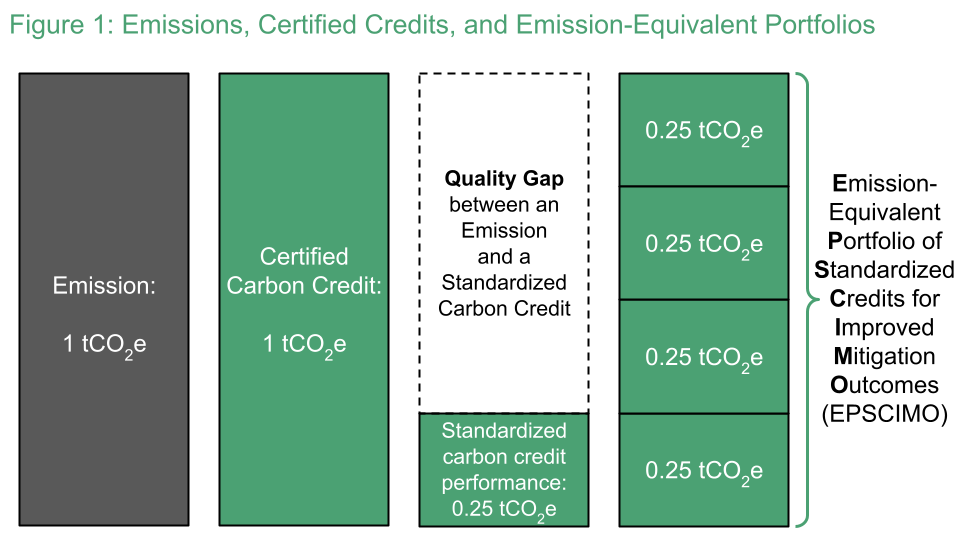

Quality is tricky to define for carbon credits. Here’s a footnote with an analogy about engineered tolerance and size2. Instituting a quality metric such that each 1tCO2 emitted is neutralized with a stack of credits that offer the same degree of certainty is analogous to accounting for non-permanence, but includes other quality factors. Although 1tCO2 of tree planting isn’t equivalent to 1tCO2 from coal combustion, maybe 4tCO2 or 10tCO2 of tree planting would suffice. The market needs a mechanism to offset an emission with an “emission-equivalent portfolio of standardized credits for improved mitigation outcomes”, or EPSCIMOs3.

By taking responsibility for solving the equivalence problem, buy-side commodification eliminates the fallout caused from imperfect supply. That’s not to say suppliers would be let off the hook – part of the commodification metrics would have to include historic supplier performance and contemporaneous measurement certainty.

Buy-side commodification of credits also offers markets the opportunity to improve credit supply over time by eliminating the worst performing credit or project types. This resembles the recent changes of carbon markets to de-list renewable energy from certified supply due to poor credit quality. Enforcing a credit quality cutoff that strengthens over time enables markets to dynamically improve average supply quality4. As project data is collected over time, the carbon market would align with the most efficacious climate results.

Buy-side standardization of the carbon markets has radical importance for effective climate action. However, it would fundamentally change pricing dynamics. Here’s a quick list of expected changes or side-effects:

The market would have to supply multiple low-quality credits to generate a single high-quality EPSCIMO.

Like other commodities, EPSCIMO pricing would be less volatile for offsetters, less dependent on supply origin

However, EPSCIMO prices would be higher than offsetters typically pay for credit supply5.

Higher EPSCIMO prices seem acceptable since buyers would likely value the reduced/eliminated reputational risk of buying low-quality carbon credits, but significantly higher prices might reduce demand for credit supply6.

Today the ‘portfolio approach’ to carbon credits is often suggested as a way to mitigate risk while delivering the best outcomes in an unknown CDR supply future. Standardizing aggregated credits would deliver high-quality, cost-effective climate action while simplifying portfolio risk reduction.

An interesting artifact of instituting this quality-first carbon accounting exercise is that it would immediately provide a market-based value proposition for carbon negativity, not just carbon neutrality. The commodified EPSCIMO product would necessarily include the purchase of an excess of credits to account for any future losses of permanence or improper baselining. Buyers could confidently claim they reached ‘net-zero emissions’. However, the over-purchase / over-generation of credits to ensure 1-for-1 quality would mean a perpetual excess of carbon negativity – a carbon negativity reserve, you might say.

In the coming weeks I plan to publish a transparent mathematical framework for buy-side commodification of carbon credit quality. To that end, I’ve built a beta version and would love to have testers provide initial feedback and input. I’ll publish the quality framework in due course, but will accelerate publication if you think this is important and worth sharing. Click the button to fix carbon markets!

UPDATE (4/26/2023):

The US Bipartisan Policy Center with Carbon Direct just published a report on Government Intervention in Support of Quality Carbon Credits. It describes approaches the government might take to foster high-quality carbon credits with 5 scenarios. This post is in line with Scenario 4 in which the VCM self-regulates the framework for credits through an "SRO"7.

The federal government could help facilitate the formal designation of a self-regulated compliance framework for registries and market actors. For example, one or more self-regulatory organizations (SRO) could be formed; these SROs would be self-regulating but subject to government-backed guardrails for enforcing credit quality.

Markets that focus on the highest-quality credits, and their buyers, are to be commended for taking solids steps toward effective climate action. However, high-quality sales volumes are a tiny fraction of the broader carbon market and broader success would require 1) top-notch, global marketing or 2) a mass-education of consumers. An industry standard that fits today’s credit supply and dynamically morphs to match future high-quality supply is an important step to competing with the numerous other markets selling low-quality credits.

Nuts and bolts are a good analogy for tolerance. Nuts and bolts fit together based on the tight tolerances of machined parts. A properly functioning nut (carbon credit) and bolt (emission) pair means each is correctly measured. If an emission is 1±0.05tCO2 (5% tolerance), then a carbon credit should amount to 1±0.05tCO2. If the credit is 1±0.25tCO2 (25% tolerance), then it’s likely a poor fit with 40% of nuts being too small for the bolt.

Bricks are a good analogy for size. How many bricks does it take to build a wall? It depends on the height of the wall and the size of the brick. Let’s say the wall is 1tCO2 tall (emission). Let’s also say the brickmaker thought their bricks would be 1tCO2 tall, but the average brick size after production and installation is 0.25tCO2 tall. You would need 4 bricks to build the wall.

Ideally, a version of this mechanism will eventually be incorporated into the accounting structure of “internationally transferable mitigation outcomes” (ITMOs) established by Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Strengthening quality standards might also earn back credibility and increase demand

Despite the adverse impacts this would have on the volume of credits sought, I’m personally of the opinion that today’s credit prices are criminally inexpensive and continue to be an excuse to pollute.

Price elasticity of demand is unstudied as a function of credit quality and likely irrelevant if budgeted climate funds are put toward direct emissions reductions. This factor will likely only matter post-2030, so there is adequate time to rigorously study the impacts.

Scenario 1 and 2 are about no government involvement, or recommendations and guidance on best practices. Scenario 3 follows the TSVCM approach, with the governemnt approving certification of quality. Scenarios 1-3 are basically business as usual for the VCM. Scenario 5 is the heavy handed approach where the government directly regulates credits. I think this approach is unlikely in the US, so Scenario 4 is more important to pursue.